- Global forecast summary

- Net Zero Emissions by 2050 Scenario tracking

- Global forecast summary

- Industry

- Buildings

- Net Zero Emissions by 2050 scenario tracking

Cite report

Close dialogIEA (2024), Renewables 2023, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/reports/renewables-2023, Licence: CC BY 4.0

Copy to clipboard

Share this report

Close dialog- Share on Twitter Twitter

- Share on Facebook Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn LinkedIn

- Share on Email Email

- Share on Print Print

Report options

Close dialogElectricity

Global forecast summary

2023 marks a step change for renewable power growth over the next five years

Renewable electricity capacity additions reached an estimated 507 GW in 2023, almost 50% higher than in 2022, with continuous policy support in more than 130 countries spurring a significant change in the global growth trend. This worldwide acceleration in 2023 was driven mainly by year-on-year expansion in the People’s Republic of China’s (hereafter “China”) booming market for solar PV (+116%) and wind (+66%). Renewable power capacity additions will continue to increase in the next five years, with solar PV and wind accounting for a record 96% of it because their generation costs are lower than for both fossil and non-fossil alternatives in most countries and policies continue to support them.

Renewable electricity capacity additions by technology and segment, 2016-2028

Solar PV and wind additions are forecast to more than double by 2028 compared with 2022, continuously breaking records over the forecast period to reach almost 710 GW. At the same time, hydropower and bioenergy capacity additions will be lower than during the last five years as development in emerging economies decelerates, especially in China.

China is in the driver’s seat

China’s renewable electricity capacity growth triples in the next five years compared with the previous five, with the country accounting for an unprecedented 56% of global expansion. Over 2023-2028, China will deploy almost four times more renewable capacity than the European Union and five times more than the United States, which will remain the second- and third-largest growth markets. The Chinese government’s Net Zero by 2060 target, supported by incentives under the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) and the ample availability of locally manufactured equipment and low-cost financing, stimulate the country’s renewable power expansion over the forecast period.

Renewable electricity capacity growth in China, main case, 2005-2028

Renewable electricity capacity growth by country or region, main case, 2005-2028

Meanwhile, expansion accelerates in the United States and the European Union thanks to the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and country-level policy incentives supporting EU decarbonisation and energy security targets. In India, progressive policy improvements to remedy auction participation, financing and distributed solar PV challenges pay off with faster renewable power growth through 2028. In Latin America, higher retail prices spur distributed solar PV system buildouts, and supportive policies for utility-scale installations in Brazil boost renewable energy growth to new highs.

Renewable energy expansion also accelerates in the Middle East and North Africa, owing mostly to policy incentives that take advantage of the cost-competitiveness of solar PV and onshore wind power. Although renewable capacity increases more quickly in sub-Saharan Africa, the region still underperforms considering its resource potential and electrification needs

The forecast has been revised upwards, but country and technology trends vary

We have revised the global Renewables 2023 forecast up by 33% (or 728 GW) from our December 2022 publication. For most countries and regions, this revision reflects policy changes and improved economics for large-scale wind and solar PV projects, but also faster consumer adoption of distributed PV systems in response to higher electricity prices. Overall, China accounts for the most significant upward revisions for all technologies except bioenergy for power, for which reduced government support, feedstock limitations and complicated logistics remain challenging.

Renewable electricity capacity forecast revisions by country, 2023-2027

Renewable electricity capacity forecast revisions, 2023-2027

Despite regulatory changes to its net metering scheme, Brazil’s distributed PV capacity growth is exceeding our expectations, leading to noticeable upward revisions. For other countries, a more optimistic outlook result from policy improvements for auction design and permitting, and a growing corporate PPA market in Germany; positive impacts of IRA incentives in the United States; and speedier streamlined renewable energy auctioning in India.

Conversely, we have revised down the forecast for Korea because the government’s policy focus has shifted from renewables to nuclear energy, reducing solar PV targets. We have also reined in forecast growth for other markets compared with last year’s outlook: for Spain because renewable energy auctions have been significantly undersubscribed; for Australia due to continued policy uncertainty following early achievement of its Large-scale Renewable Energy Target (LRET); for Oman because development time frames for large-scale renewable energy projects have been longer than expected, including for green hydrogen; and for multiple Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries as a result of sustained policy uncertainty as well as overall power supply gluts limiting additional renewable deployment in the short term.

Rapid government responses to grid connection, permitting, policy and financing challenges can accelerate renewable energy growth

In the main case, taking country-specific challenges that hamper faster renewable energy expansion into account, we forecast that almost 3 700 GW of new renewable capacity will become operational worldwide over the next five years. In contrast, in our accelerated case, we assume that governments overcome these challenges and implement existing policies more quickly.

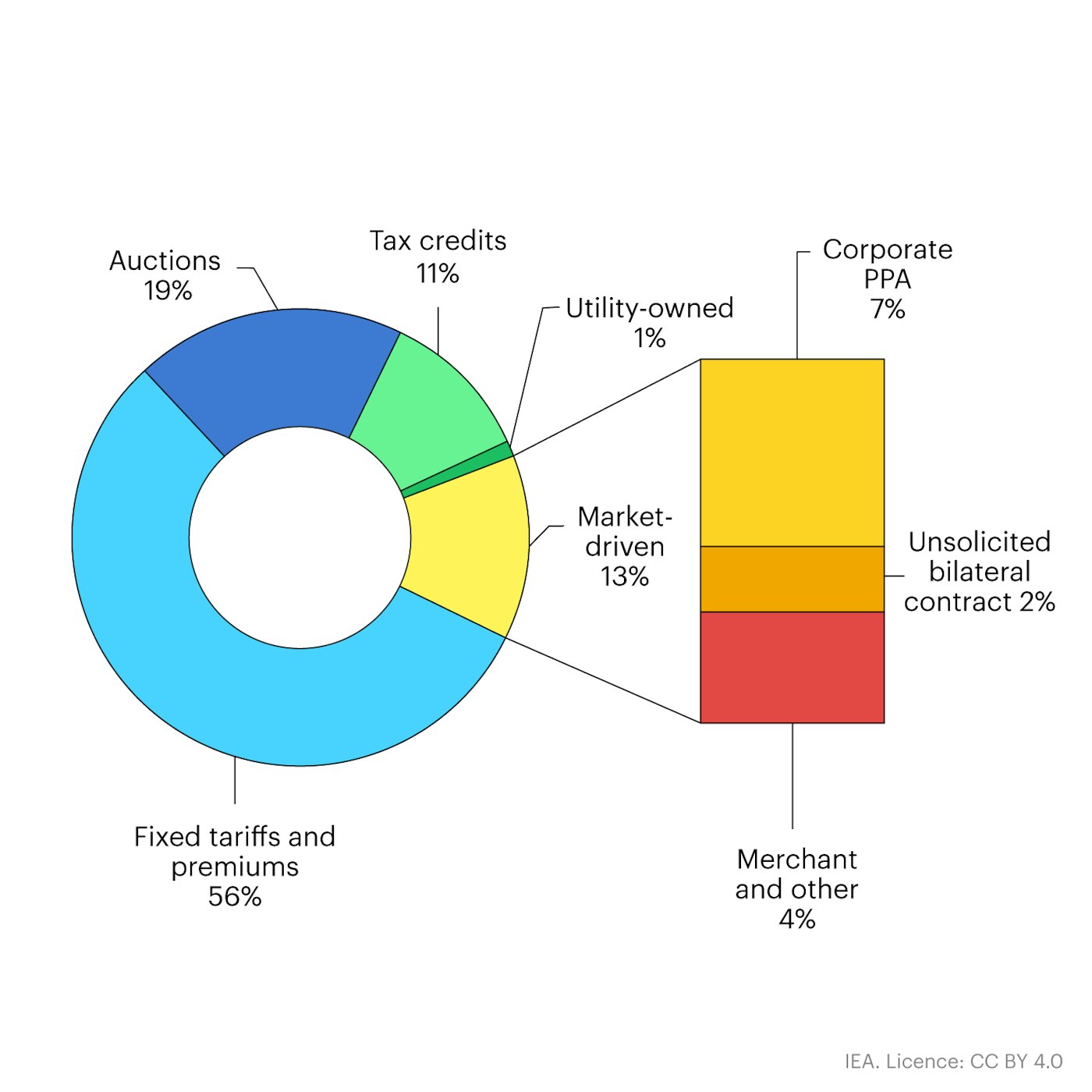

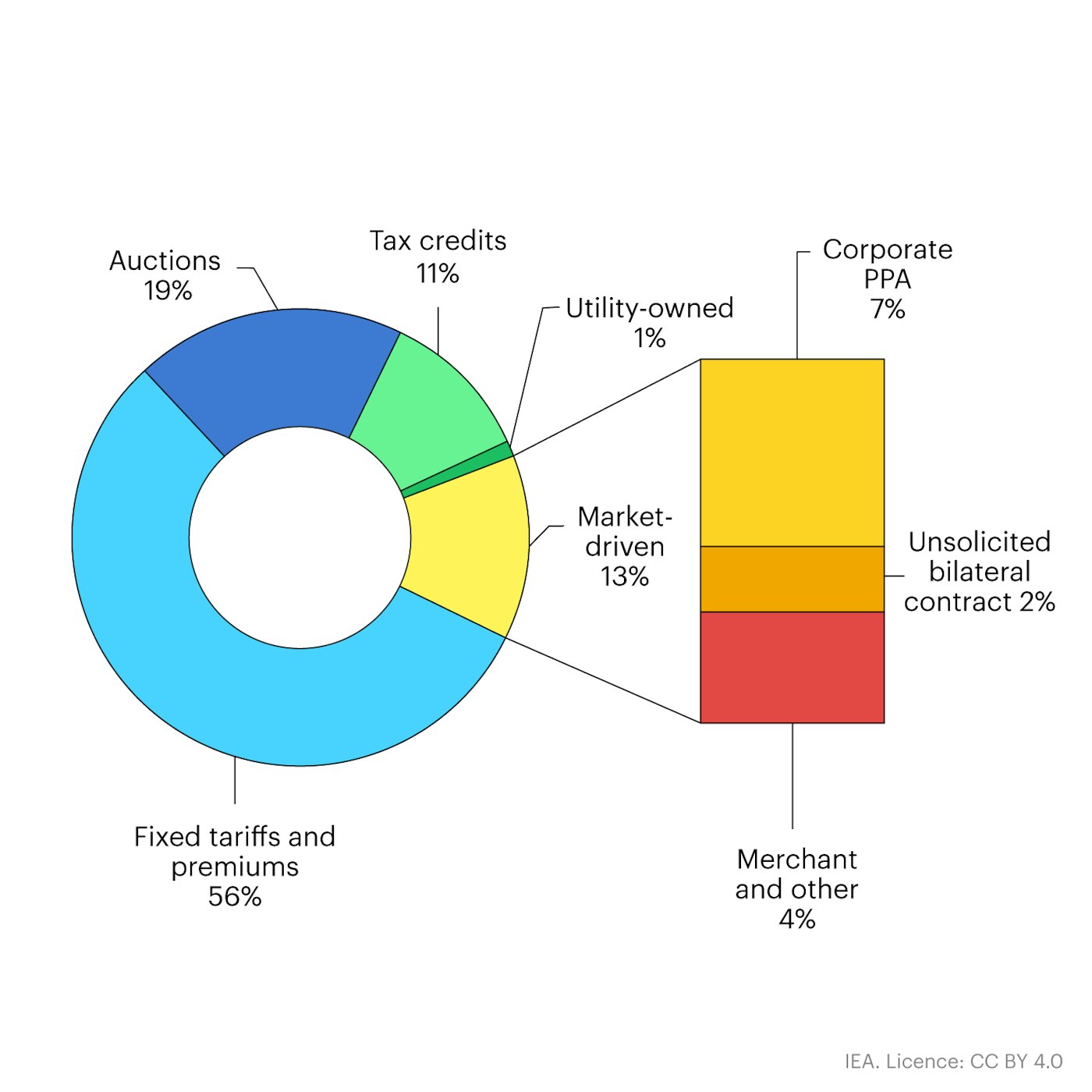

Renewable electricity capacity by primary driver, 2023-2028

These challenges fall into four main categories. First are policy uncertainties and delayed policy responses to the new macroeconomic environment, encompassing inflexible auction design. During the energy crisis, governments intervened in energy markets to protect consumers from high prices. While these interventions were justified, they also created uncertainty for investors over the future investment environment in the electricity sector. The macroeconomic changes also drove up costs and contract prices for wind and solar PV projects, and a lack of reference price adjustments and contract price indexation methodologies reduced the bankability of projects, mostly in advanced economies.

Meanwhile, emerging economies have been slow to develop strong renewable energy targets and clear incentive schemes. While renewable energy projects (especially solar PV and wind) are already more affordable than fossil fuel-based alternatives, slower-than-expected demand growth has resulted in overcapacity of young coal and gas fleets in many emerging economies, creating little need for additional capacity.

The second problem is insufficient investment in grid infrastructure, which has been preventing faster expansion. Today, more than 3 000 GW of renewable generation capacity are in grid queues, and half of these projects are in advanced stages of development.1 This challenge holds true for both advanced economies and emerging and developing countries. Development lead times for grid infrastructure improvements are significantly longer than for wind and solar PV projects.

The third challenge involves permitting. The amount of time required to obtain permits can range from one to five years for ground-mounted solar PV projects, two to nine years for onshore wind, and nine years on average for offshore wind projects. Delays resulting from complex and lengthy authorisation procedures are slowing project pipeline growth, limiting participation in renewable energy auctions, raising project risks and costs, and ultimately weakening project economics.

The fourth obstacle is insufficient financing in developing countries. Mitigating risks in high-risk countries through concessional financing continues to be challenging because of ongoing policy uncertainties and implementation challenges, for instance in Kenya, South Africa, and Nigeria. In many developing countries, government-owned utilities are under financial stress and the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) can be two to three times higher than in mature renewable energy markets, reducing project bankability. Every percentage point decline in the WACC reduces wind and solar PV generation costs by at least 8%.